Do calories in equal calories out?

A dietary Calorie (big 'C') is the amount of energy required to heat 1 kilogram of water by 1 degree Celsius. The body uses this energy to drive countless chemical reactions and bodily functions. According to advocates of the “calories in, calories out” principle, putting on weight is entirely due to eating too many calories.

'Eat less and move more' is the mainstream mantra and it’s perhaps not surprising that companies from Coca Cola to Unilever sponsor numerous think tanks, NGO’s and their associated research arms to reinforce this way of thinking.

While it is of course true to say that eating too much is related to excess calories, our bodies are not machines. You could say, for example, that aeroplanes are heavier than air so eventually they must come to the ground… but that doesn’t contribute to helping them stay safely in the air. For that you have trained pilots, sophisticated electronics, new wing shapes that provide more lift, flaps to alter those lift characteristics and increasingly advanced aerodynamics. For us, the quality and diversity of what we eat and the many effects from building bones to regulating hormones are as important (or more so) as the quantity. It doesn’t take a scientist to realise that one 125 gram Mars bar will affect you differently than 125 grams of broccoli.

A kilo of fat is usually calculated at between 7,000 and 8,000 calories, with protein and carbs containing less than half that impact, so it’s not surprising that ‘calorie controlled diets’ have it in for fat. Such diets ignore what makes you feel full over longer periods of time for example. But the simple idea that all calories are created equal is just plain naïve: different types of cooked and uncooked food with their different metabolic pathways affect our bodies in many different ways. Counting calories may make you feel good because you feel you're in control... but you are not.

'Eat less and move more' is the mainstream mantra and it’s perhaps not surprising that companies from Coca Cola to Unilever sponsor numerous think tanks, NGO’s and their associated research arms to reinforce this way of thinking.

While it is of course true to say that eating too much is related to excess calories, our bodies are not machines. You could say, for example, that aeroplanes are heavier than air so eventually they must come to the ground… but that doesn’t contribute to helping them stay safely in the air. For that you have trained pilots, sophisticated electronics, new wing shapes that provide more lift, flaps to alter those lift characteristics and increasingly advanced aerodynamics. For us, the quality and diversity of what we eat and the many effects from building bones to regulating hormones are as important (or more so) as the quantity. It doesn’t take a scientist to realise that one 125 gram Mars bar will affect you differently than 125 grams of broccoli.

A kilo of fat is usually calculated at between 7,000 and 8,000 calories, with protein and carbs containing less than half that impact, so it’s not surprising that ‘calorie controlled diets’ have it in for fat. Such diets ignore what makes you feel full over longer periods of time for example. But the simple idea that all calories are created equal is just plain naïve: different types of cooked and uncooked food with their different metabolic pathways affect our bodies in many different ways. Counting calories may make you feel good because you feel you're in control... but you are not.

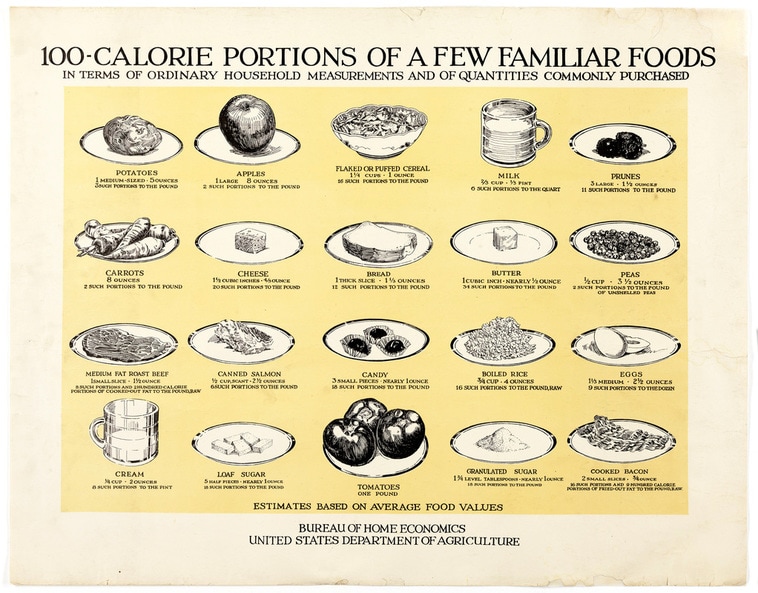

This 1930's poster shows how the US government tried to educate the populace

This 1930's poster shows how the US government tried to educate the populace

Since the 1970's we've received the message that low-fat versions of our favourite foods are supposed to reduce the total number of calories we eat and, taken in isolation, they do. Gram for gram, low-fat milk contains fewer calories than does whole milk. But the idea that drinking lower-calorie drinks of any sort leads to lower-calorie intake overall appears to be flawed.

Reduced-fat foods and drinks may not be as filling, so people end up compensating for this and eating or drinking more. Robert Ludwig’s research into food addictions is at first somewhat counter-intuitive – at least to people growing up today. The results support the theory that foods with a high-glycemic index, such as breads and bagels, white rice and instant oatmeal also increase hunger and contribute to weight gain; but there is no such association with that declining sector, whole milk.

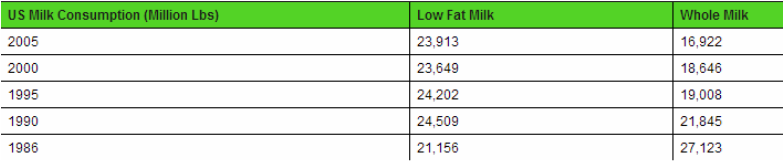

According to US statistics, whole milk consumption declined a full 33% from 1970 to 2005, while sales of lower-fat milks doubled during that time frame.

Reduced-fat foods and drinks may not be as filling, so people end up compensating for this and eating or drinking more. Robert Ludwig’s research into food addictions is at first somewhat counter-intuitive – at least to people growing up today. The results support the theory that foods with a high-glycemic index, such as breads and bagels, white rice and instant oatmeal also increase hunger and contribute to weight gain; but there is no such association with that declining sector, whole milk.

According to US statistics, whole milk consumption declined a full 33% from 1970 to 2005, while sales of lower-fat milks doubled during that time frame.

And indeed, butter consumption also dropped steadily throughout the 20th century, as more cooks switched to margarine or liquid cooking oils. They were cheaper to buy and recommended by ‘experts’ as a healthier choice – also bringing in huge profits to those manufacturing them; much more money than you can ever earn with relatively unprocessed milks and butters.

The end result? The ongoing demonization of fat has led to most of the milk that we drink today being of the low-fat variety. You may think that’s OK and that de-fatting is maybe a natural process? Don’t the producers just skim the fat off the surface?

But it’s a concern; paediatricians routinely recommend skim and low-fat to help parents control their children’s calories. In fact, they’re the only types of milk available in New York City’s public school system. Only pre-Kindergarten children are allowed to have whole milk.

Taking a step back: Fat isn’t making us fat. Restricting calories, we now know, only leads to temporary weight loss as your metabolism adjusts to weight-loss by slowing down. CW (Conventional Wisdom) is slowly changing; albeit very slowly… back to Professor Walter Willet, “Diets high in fat do not appear to be the primary cause of the high prevalence of excess body fat in our society, and reductions in fat will not be a solution.” He is cautious in his choice of words!

The end result? The ongoing demonization of fat has led to most of the milk that we drink today being of the low-fat variety. You may think that’s OK and that de-fatting is maybe a natural process? Don’t the producers just skim the fat off the surface?

But it’s a concern; paediatricians routinely recommend skim and low-fat to help parents control their children’s calories. In fact, they’re the only types of milk available in New York City’s public school system. Only pre-Kindergarten children are allowed to have whole milk.

Taking a step back: Fat isn’t making us fat. Restricting calories, we now know, only leads to temporary weight loss as your metabolism adjusts to weight-loss by slowing down. CW (Conventional Wisdom) is slowly changing; albeit very slowly… back to Professor Walter Willet, “Diets high in fat do not appear to be the primary cause of the high prevalence of excess body fat in our society, and reductions in fat will not be a solution.” He is cautious in his choice of words!

Coca-Cola now in the low-fat milk business

Coca-Cola now in the low-fat milk business

Can I have some more please?

So are our overweight problems around the world more to do with us not feeling full when we eat and drink low-fat/no-fat stuff? Fats trigger the release of cholecystokinin in the small intestine telling you your body is full and more and more research now supports the fact that animal fat is healthy for you. So, put simply, the higher levels of fat in whole milk products may be making us feel fuller, faster. Perhaps that’s why recent research shows that drinking low-fat milk may actually contribute to obesity!

A recent study published in the European Journal of Nutrition, is a meta-analysis of 16 separate observational studies and reviews the hypothesis that high-fat dairy foods contribute to obesity and heart disease risk. The reviewers conclude that there is no evidence to support this hypothesis and that in most of the studies, high-fat dairy was in fact associated with a lower risk of obesity.

"I would say it's counterintuitive," says Greg Miller, executive vice president of the US National Dairy Council. "We continue to see more and more data coming out [finding that] consumption of whole-milk dairy products is associated with reduced body fat," Miller says. "There may be bioactive substances in the milk fat that may be altering our metabolism in a way that helps us utilize the fat and burn it for energy, rather than storing it in our bodies," Miller says.

My personal thoughts... low-fat and fat-free dairy products use skimmed milk that requires the addition of synthetic and processed additives to make it the nutritional equivalent of what it once was - whole milk. But nutritional equivalence isn’t biological equivalence. For now, we don’t know a lot about this difference but it’s certainly something I consider every time I drink some refreshing whole milk.

So are our overweight problems around the world more to do with us not feeling full when we eat and drink low-fat/no-fat stuff? Fats trigger the release of cholecystokinin in the small intestine telling you your body is full and more and more research now supports the fact that animal fat is healthy for you. So, put simply, the higher levels of fat in whole milk products may be making us feel fuller, faster. Perhaps that’s why recent research shows that drinking low-fat milk may actually contribute to obesity!

A recent study published in the European Journal of Nutrition, is a meta-analysis of 16 separate observational studies and reviews the hypothesis that high-fat dairy foods contribute to obesity and heart disease risk. The reviewers conclude that there is no evidence to support this hypothesis and that in most of the studies, high-fat dairy was in fact associated with a lower risk of obesity.

"I would say it's counterintuitive," says Greg Miller, executive vice president of the US National Dairy Council. "We continue to see more and more data coming out [finding that] consumption of whole-milk dairy products is associated with reduced body fat," Miller says. "There may be bioactive substances in the milk fat that may be altering our metabolism in a way that helps us utilize the fat and burn it for energy, rather than storing it in our bodies," Miller says.

My personal thoughts... low-fat and fat-free dairy products use skimmed milk that requires the addition of synthetic and processed additives to make it the nutritional equivalent of what it once was - whole milk. But nutritional equivalence isn’t biological equivalence. For now, we don’t know a lot about this difference but it’s certainly something I consider every time I drink some refreshing whole milk.