A US historical perspective abbreviated from Gary Taubes

Your brain is more than 60% fat

Your brain is more than 60% fat

The U.S. Surgeon General's Office set off in 1988 to write the definitive report on the dangers of dietary fat; four years earlier in 1984, the National Institute of Health (NIH) had begun advising every American old enough to walk to restrict fat intake. The president of the American Heart Association told Time magazine that if everyone went along, "we will have atherosclerosis (the hardening and narrowing of the body’s arteries) conquered" by the year 2000. The Surgeon General's Office itself had just published its 700-page landmark "Report on Nutrition and Health," declaring fat the single most unwholesome component of the American diet. So the scientific task appeared straightforward.

Finally, in June 1999, 11 whole years after the project had begun, the Surgeon General's Office circulated a letter, authored by the last of the project officers, explaining that the report would be dropped. As the Surgeon General's Office discovered, the science of dietary fat is not nearly as simple as it had once appeared. The proposition, now over 60 years old, that dietary fat is detrimental to your health is based on research that showed a correlation between saturated fat found primarily in meat and dairy products and elevated blood cholesterol levels. As a result, clogged arteries (atherosclerosis) would lead to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, heart attack and untimely death. Sounds familiar and logical… doesn’t it?

Looking back on this today, the jury is still out on whether low-fat diets have any benefit for healthy people. But what has resulted from the resulting demonization of fat is that a shift has taken place towards high-carbohydrate diets, which may well be much worse for you than high-fat diets.

Finally, in June 1999, 11 whole years after the project had begun, the Surgeon General's Office circulated a letter, authored by the last of the project officers, explaining that the report would be dropped. As the Surgeon General's Office discovered, the science of dietary fat is not nearly as simple as it had once appeared. The proposition, now over 60 years old, that dietary fat is detrimental to your health is based on research that showed a correlation between saturated fat found primarily in meat and dairy products and elevated blood cholesterol levels. As a result, clogged arteries (atherosclerosis) would lead to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, heart attack and untimely death. Sounds familiar and logical… doesn’t it?

Looking back on this today, the jury is still out on whether low-fat diets have any benefit for healthy people. But what has resulted from the resulting demonization of fat is that a shift has taken place towards high-carbohydrate diets, which may well be much worse for you than high-fat diets.

|

A little history

The true history of this (originally) US-based conviction that went on to conquer the world, namely that dietary fat is deadly, is one in which politicians, bureaucrats, the media, and the public have played just as large a role as the scientists and the science. It's a story of what can happen when the demands of public health policy and the public requirement for simple advice-run up against the confusing ambiguity of real science. That being said, ‘fat is bad for you’ has evolved from hypothesis to accepted dogma worldwide. Only now are things slowly and for many reluctantly beginning to change. By 1969, the state of the science could still be summarized by a single sentence from a report of the Diet-Heart Review Panel of the National Heart Institute: "It is not known whether dietary manipulation has any affect whatsoever on coronary heart disease." The chair of that panel was "Pete" Ahrens, whose laboratory at Rockefeller University in New York City did much of the early research on fat and cholesterol metabolism. Whereas early proponents of low-fat diets were concerned primarily about the effects of dietary fat on cholesterol levels and heart disease, Ahrens and his panel of 10 experts in clinical medicine, human nutrition and metabolism were equally concerned that eating less fat could have profound effects throughout the body, many of which might be harmful. The brain, for instance, is 70% fat. Fat is also the primary component of all cell membranes. Even tampering with the proportion of saturated to unsaturated fats in the diet changes the fat composition of these membranes and leads potentially to a change in membrane permeability, controlling the transport of everything from glucose, signalling proteins and hormones to bacteria, viruses, and tumour-causing agents in and out of the cell. It was in the year of flower-power, 1968, that Senator George McGovern's bipartisan Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs began almost single-handedly to change US nutritional policy and initiated the process of turning the dietary fat hypothesis into dogma. Dietary fat played no role in the committee’s original mandate which was to eradicate malnutrition in America and it instituted a series of landmark federal food assistance programs. But the malnutrition work began to peter out in the mid-1970s and because the committee didn't disband, its general counsel, Marshall Matz, and staff director Alan Stone, both young lawyers, decided that the committee should address other issues. The First Dietary Guidelines In July 1976, McGovern's committee listened to 2 days of testimony on diet and disease. Following that session, Nick Mottern, a former journalist for The Providence Journal, was the person assigned the task of writing the first "Dietary Goals for the United States." Although he had no scientific background and no experience writing about science, nutrition, or health, he believed that these new Dietary Goals would launch a "revolution in diet and agriculture in this country." As he wrote, his primary additional source for input on the subject of dietary fat was the Harvard School of Public Health nutritionist, Mark Hegsted. Hegsted who had studied fat and cholesterol metabolism in the early 1960s believed unconditionally in the benefits of restricting fat intake, although he says he was aware that at the time, his was an extreme opinion. Mottern came to see dietary fat as the nutritional equivalent of cigarettes, and the food industry as akin to the tobacco industry in its willingness to suppress scientific truth in the interests of profits. To Mottern, those scientists who spoke out against fat were those willing to take on the industry. "It took a certain amount of guts to speak about this because of the financial interests involved", he is quoted as saying. Mottern's report suggested that Americans cut their total fat intake to 30% of the calories they consume and saturated fat intake to 10%, in accordance with AHA recommendations for men at high risk of heart disease. The report acknowledged the existence of controversy but insisted Americans had nothing to lose by following its advice. "The question to be asked is not why should we change our diet but why not?" wrote Hegsted in the introduction. "There are no risks that can be identified and important benefits can be expected." This was an optimistic but still debatable position, and when Dietary Goals was released in January 1977, "all hell broke loose," recalls Hegsted. "Practically nobody was in favour of the McGovern recommendations. Damn few people." There followed 7 years of controversy. Prominent scientists spoke out, including Ahrens of the National Heart Institute who testified that advising Americans to eat less fat on the strength of marginal evidence was equivalent to conducting a nutritional experiment with the American public as subjects. Even the American Medical Association protested, suggesting that the diet proposed by the guidelines raised the "potential for harmful effects." Representatives from the dairy, egg and cattle industries also vigorously expressed their opposition to the guidelines for obvious reasons. And it was this juxtaposition of health experts and food industry lobbyists which served to taint the scientific criticisms: the scientists who argued against the committee's guidelines were portrayed as being either hopelessly behind the times, or industry apologists, if not both. The first edition of "Using the Dietary Guidelines"

The Dietary Goals guidelines might still have died a quiet death when McGovern's committee came to an end in late 1977 if two federal agencies had not felt the need to respond. Although they took contradictory points of view, one message with media assistance won out. The first was the Department of Agriculture (USDA), where consumer/activist Carol Tucker Foreman had recently been appointed an assistant secretary. Foreman believed that the USDA should turn McGovern's recommendations into official policy, and she was not deterred by the existence of scientific controversy. "I have to eat and feed my children three times a day, and I want you to tell me what your best sense of the data is right now", she would tell scientists. The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences which decides the Recommended Dietary Allowances, would have been a natural choice, to prepare such guidelines but their President, Philip Handler, an expert on metabolism, had called Mottern's Dietary Goals "nonsense." So Foreman turned to McGovern's staffers for advice and they recommended she hire Hegsted, which she did. Hegsted relied on a state-of-the-science report published by an expert but very divergent committee of the American Society for Clinical Nutrition. "They were nowhere near unanimous on anything," says Hegsted, "but the majority supported something like the McGovern committee report." The resulting document became the first edition of "Using the Dietary Guidelines for Americans." Although this first edition acknowledged the existence of controversy and suggested that a single dietary recommendation might not suit an entire diverse population, the advice to avoid fat and saturated fat was, indeed, virtually identical to McGovern's Dietary Goals. Yet, three months later, the NAS Food and Nutrition Board released its own guidelines: "Toward Healthful Diets." Controversially, their conclusion was that the only reliable advice for healthy Americans was to watch their weight; everything else, dietary fat included, would take care of itself. Media reports strongly criticized the NAS advice for conflicting with the USDA's and McGovern's report and their guidelines were positioned as being irresponsible. Supporting scientific evidence was still hard to find but fat was still the number one enemy. The proposition that dietary fat also caused cancer gained ground during the late 1970s and by 1982, the evidence supporting this idea was thought to be clear. So undeniable indeed that a landmark NAS report on nutrition and cancer equated those researchers who remained skeptical with "interested parties who formerly argued that the association between lung cancer and smoking was not causational." Yet by the year 2000 and hundreds of millions of research dollars later, a similarly massive expert report by the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research could find neither "convincing" nor even "probable" reason to believe that dietary fat caused cancer. Healthy or not? Saturated fat was seen as the worst offender, but to understand the complexity, consider a piece of steak - to be precise, a porterhouse, select cut, with a half-centimeter layer of fat, the nutritional constituents of which can be found in the Nutrient Database for Standard Reference at the USDA Web site. After grilling, this porterhouse reduces to a serving of almost equal parts fat and protein. 51% of the fat is mono-unsaturated and of that, virtually all (90%) is oleic acid, the same healthy fat you find in olive oil. Saturated fat constitutes 45% of the total fat, but a third of that is stearic acid, which is, at the very least, harmless. The remaining 4% of the fat is polyunsaturated, which improves cholesterol levels. In sum, well over half-and perhaps as much as 70% of the fat content of a porterhouse steak will improve cholesterol levels compared to what they would be if bread, potatoes, or pasta were consumed instead. The remaining 30% will raise LDL cholesterol but will also raise HDL… All of which suggests that on balance, eating a porterhouse steak rather than a bowl of pasta might actually improve heart disease risk. The law of unexpected consequences Margarine sales went up, perhaps not surprisingly, yet studies that emerged in the later part of 20th century began to show that the trans fatty acids found in most margarines are unhealthy. Still today, many Americans don’t eat butter because of the cumulative impact of all those messages over the years telling them that the saturated fats in butter might kill them. The other trade-off in the plus/minus problem of human diets is carbohydrates. When the, federal government began pushing low-fat diets, the scientists and administrators hoped that Americans would replace fat calories with fruits and vegetables and legumes, but it didn't happen. If nothing else, economics worked against it. The food industry has little incentive to advertise non-proprietary items such as broccoli. Instead the great bulk of the $40 billion plus spent yearly on food advertising goes to selling carbohydrates in the guise of fast-food, sodas, snacks, and candy bars. Much of the food industry, although not all, is still benefiting from the opportunity to use public health messages as marketing. Carbohydrates are what Harvard's Willett calls the flip side of the calorie trade-off problem. Because it is exceedingly difficult to add pure protein to a diet in any quantity, a low-fat diet is, by definition, a high-carbohydrate diet, just as low fat cookies or yogurt are, by definition, high in carbohydrates. Numerous studies suggest that high-carbohydrate diets can raise triglyceride levels, create small, dense LDL particles, and reduce HDL; and that’s a combination which often leads to a condition known as "insulin resistance" or “metabolic syndrome” which is very much on the rise today. The Greatest Scam in the History of Modern Medicine |

A puritan angle?

Dr John Powles of the School of Clinical Medicine at Cambridge University is on record as saying that the anti-fat movement was founded on the Puritan notion that "something bad had to have an evil cause, and you got a heart attack because you did something wrong, which was eating too much of a bad thing, rather than not having enough of a good thing."

He may have a real point. Consider these words from Anne Parone who wrote the bestseller, ‘Chic and Slim’ back in 2002. "Blame it on the Puritans - If you wonder why the French, the most food-obsessed people on the planet, can eat all that cream, butter, and egg yolks and struggle far less with excess weight than Americans who dutifully take home shopping bags of sugarless and fat-free, the answer is that the French never had any Puritans; they had Joan of Arc, Napoleon Bonaparte, Charles de Gaulle, and Brigitte Bardot. But no Puritans.” High insulin levels are bad for youHigh levels of insulin increase delta-5 desaturase. So what you might ask? Well, delta-5 desaturase helps convert omega 6 fatty acids derived from the linoleic acid in grain and vegetable oils into arachidonic acid.

Higher levels of arachidonic acid lead to increased inflammatory prostaglandins and this, according to Gary Taubes, is not a good thing. He suggests that it may be the reason that obesity is associated with disease, saying “what makes you fat makes you sick”. Also associated with high levels of insulin is a substance called anandamide, a chemical affecting the same receptor in the brain that THC does (the active ingredient in drugs such as Cannabis). So our carb-rich, grain based Western diet also has a potential influence on the endocannabinoid system which affects a variety of physiological processes including appetite, pain-sensation, mood and memory. In a nutshell, eating foods high in insulin-raising grain content and sugar leads to both inflammatory results and contributes to a self-perpetuating cycle of overeating and increased appetite. Wise words from 400 BC

"Let your food be your medicine, and your medicine be your food." Hippocrates.

Gary Taubes, who wrote the original full-length version of the article to the left is a science and health journalist but he recently co-founded the Nutrition Science Initiative. Its mission is to reduce the individual, economic and social toll of obesity and its related diseases by improving the quality of science in nutrition and obesity research. The problem as NUSI sees it is: "We keep getting fatter and diabetes rates are skyrocketing. One possible explanation is that we’re getting the wrong advice. Official dietary guidelines are not based on rigorous science. They may be contributing to the problem and doing far more harm than good." It's a great initiative with much more at: http://nusi.org/

Summary

The simple fact is that the same basic advice continues to be given by doctors, nutritionists and dietitians around the world... Eat less fat. The logic underlying population wide recommendations such as the latest USDA Dietary Guidelines is that limiting saturated fat intake, even if it does little or nothing to extend the lives of healthy individuals and even if not all saturated fats are equally bad, might still delay tens of thousands of deaths each year throughout the entire country. Limiting total fat consumption is considered reasonable advice because it's simple and easy to communicate and understand, and it may help limit calorie intake. This, in spite of the rapidly growing obesity and diabetes levels in all westernised countries. Whether it's scientifically justifiable may simply not be relevant. "When you don't have any real good answers in this business," says Krauss, "you have to accept a few not so good ones as the next best thing." |

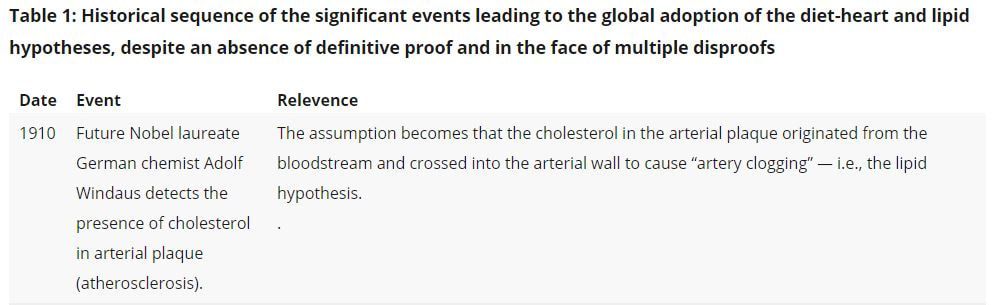

For a more authoritative read, and a great history timeline, try Professor Tim Noakes 2020 series at Cross-Fit. He provides a brilliant overview of how we got to where we are today - a series of assumptions mixed with associational evidence, that became mis-used to benefit egos and large corporations, and arguably caused more death and chronic disease than many wars.

https://www.crossfit.com/health/ancel-keys-cholesterol-con-part-2-2

Table 1, item 1 from the year 1910 is where it all begins.

https://www.crossfit.com/health/ancel-keys-cholesterol-con-part-2-2

Table 1, item 1 from the year 1910 is where it all begins.